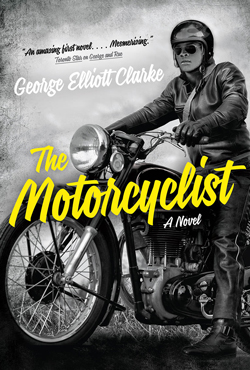

The Motorcyclist

The Motorcyclist

By George Elliot Clarke

Toronto: Harper Collins, 2016

ISBN-10: 1443445134

ISBN-13: 978-1443445139

Carl, a young black man, a motorcyclist, artist and womanizer, is caught between the expectations of his times and the possibilities of life. He is trapped in a railway worker’s pedestrian existence—a life from which his motorcycle (a BMW R69 named ‘Liz II’ in honor of Queen Elizabeth II), the open road and, most notably, his sexual exploits with numerous women, both black and white, provide freedom and happiness. Carl’s story is told in George Elliot Clarke’s novel The Motorcyclist—a series of vignettes set in 1959 in racially-divided Halifax, Nova Scotia and based loosely on the diary of Clarke’s father. The narrative consists not of plot and dialogue, but mostly of Carl’s inner thoughts. Clarke, Canada’s poet-laureate and a University of Toronto professor, writes with sensual language both beautiful and raw. The Motorcyclist abounds with poetic metaphors like this: when Carl wheels his motorcycle out of storage he is “like a groom takin’ his bride down the aisle” (10). The wording is at times so richly inventive and linguistically complex that it is best read in small units, a few pages at a time. Readers should expect to slow down and enjoy the lyricism of the text.

I read this book with two eyes—a motorcyclist’s eye and a philosopher’s eye. First, the motorcyclist’s report. Clarke does not ride and has only been a motorcycle passenger once or twice, and yet The Motorcyclist contains fine descriptions of the experience of motorcycling and presents riding as a metaphor with lessons for life.

“You can’t daydream when it comes to navigating a motorcycle” (3). Riding—like life—requires mindfulness, having your wits about you. On a motorcycle mindlessness mean death; riding requires being fully attentive and responsive to the world, it demands a disciplined mental focus that is aware of everything around one. Motorcycles bring a person into the moment, into an embodied state of awareness and a sharpening of the senses.[1] If the rider becomes “too blissful to proceed with due caution” then tragedy can strike (104).

In order to ride safely “you need…a clear eye to avoid the random annihilations that pavement permits” and “you need a steady hand…to steer yourself over that tough surface.” One skill—intellectual or executive—without the other is not enough. In the same way, knowing how to live well and doing the things that conduce to long-run happiness are both necessary conditions of flourishing—of navigating life to “intact arrive,” as Carl puts it (4).

What can ‘throw you for a loop’ when riding is “the cemetery at the end of it all” (4). Awareness of danger is inherent in motorcycling, where life is held out over death, where we court the mortality that always shadows us.[2] When a buddy, riding recklessly, collides with a car and is killed, “Carl wept. For his dead friend. For joy too…, for he had staved off the cancellation of his own breathing” (106). Later, watching another friend crash and die puts Carl “face to face…with…unfixable wounds”—reminding him that “life seems a movement of inescapable and insistent corrosion and collapse” (182). Still later, yet another acquaintance, showing off, “lunges ahead, but his bike hits a watery patch and mutinies…. Out it scrambles from under him.” This death leaves Carl feeling “weirdly disassembled himself” by the contingency of life (a random puddle on a dry road brings demise) and the fragility of existence (that he, too, could be gone in an instant—229–230). As a memento mori—‘remember you will die’—activity, the awareness of death that riding brings also gives us wisdom for living, for setting priorities, for living authentically.

Riding is a mixture of joy and fear—as he races a friend “its fun, but Carl’s also nervous” (228). Pleasure and danger, ecstasy and risk, go together. Carl himself crashes; after tumbling through the air “he lands…on his feet, amazingly upright, whole and conscious”—and, best of all, his cycle “is undamaged” (101; cf. 146–147). Riding, like life, is often “windy going…, pitching against wind and traffic;” it presents challenges against which we, like a rider, must “pitch forward” (17). Sometimes we fail and fall—we drop the bike, but survive. “Thanks to agility, if not God-granted miracles, he’s…landed on his feet…following his motorcycle spills” (196). Dumping the bike does not stop Carl from riding—just like mistakes and setbacks in life must not keep us from getting up, dusting ourselves off and moving on with resilience.

Riding is a very physical experience. Carl’s motorcycle “connects him to the world: his feet are bare inches from pavement…; the wind licks him with rain and peppers him with bugs; the sun heats even as the breeze cools” (14). Out in the country his bike “soars up and down hills, granting…a split-second feeling of floating”—a sense of “insurgent Joy” (194). Riding is also a very physical activity. Carl becomes an “extension of the muscular machine”—“his driving merges boxing and ballet” (14). As he moves with it, leans with it, he feels one with the bike—as well as one with the elements of road, wind, sun and bugs.[3] “Astride the BMW, even when he’s bent over the fuel tank, trying to duck the tonguing wind that washes under, over, around his helmet and his jacket, Carl feels erect, like a gunfighter in full gallop, streamlining with his stallion…. His legs are sturdy wishbones and his arms are…outstretched and steel hard.” Riding is even a sexual experience. When riding his “motorcycle as jockstrap” Carl’s “manhood…is cocked” (85–86). The wind “touches intimately, even whistling about your crotch, for no denim or leather can resist its fluid penetration” (4). And dual riding with a woman is “nigh conjugal” as Carl and his girls lean together, her arms gripping his waist tightly (18).

Both at rest and in motion motorcycles are beautiful works of art which evoke an aesthetic response.[4] Carl’s bike “gleams gorgeous, in that violet paint and loud, spanking chrome…huge black fenders…[and] lean power.” “Hotly, the trim machine glitters. The tail lights, bunched together, offer a cornucopia of potential directions. Yet the R69 is sleek, clear of unnecessary ornament, save for the saddlebags, which Carl has decorated to accent the aerodynamic aesthetic of her suspension, engine and exhaust. Liz II is as intricate as a lithe, nimble insect…. Carl relishes the ingenious poise of pistons and gears, the innumerable Eiffel Towers figured in the wheel spokes” (11–12). Beyond its appearance, the motorcycle’s sounds are also pleasing: “the bike contraltos beautifully. The wheels and engine growl wolves’ vowels” (179). His rides are mechanically smooth: “the engine gallops up to 35 horsepower at 6800 rpm, thus yielding exceptional glide…. Carl is thankful for the noiseless helical gear train for the camshaft, magneto, and oil-pump drive, mechanics that give him a machine quieter than other bikes” (109). A beautiful motorcycle—a blending of art and engineering—is an object in which to become aesthetically absorbed.

The Motorcyclist accurately and insightfully depicts many aspects of riding.

Now the philosopher’s report. The Motorcyclist explores existentialist themes—freedom of choice and life as a creative work of art—as reflected in the icon of the motorcycle as a refusal of social conformity and personal boundaries. What Carl, as a black man, seeks is not just social freedom (though that would be nice, since he could be lynched for bedding a white lover) or economic freedom (it would also be nice to break out of his mundane working class job). What Carl seeks is existential freedom. Jean-Paul Sartre contrasts two philosophies of life.[5] ‘Essence before existence’ means that our future destinies are decided for us by factors outside our control. This is the condition of objects; things like motorcycles have no choice, no freedom. Carl’s BMW is predetermined to be what it is—its future is closed and it cannot change itself into a Harley-Davidson or Triumph Bonneville. ‘Existence before essence,’ however, means that our futures are not assigned in advance but decided by us through the choices we make. This is the condition of human beings; persons like Carl are not born with a specific purpose or particular destiny. Our futures are open and we determine our own life paths. This means that we bear complete responsibility for what we make of our lives—and when the full weight of this responsibility hits us (a reaction Sartre calls ‘anguish’), we want to run away from it. We can deny responsibility for how our lives go, choosing in ‘bad faith’ to be a victim, follow the crowd, make excuses and shift responsibility to outside forces that determine our lives—but doing so turns us into objects with closed futures. Or we can accept responsibility for our lives, choosing in ‘good faith’ to make hard choices and take charge of our lives, to realize that our futures are open and that we—like Carl—are in the rider’s seat. Sartre acknowledges that we all have histories—circumstances not of our own making that constrain our choices. Biological limitations (Carl is a black man not a white woman) and historical facts (Carl is the son of a single mom living in a racist society) are outside conditions that influence the options available to us. But these facts can never become excuses. Accepting freedom and responsibility, Sartre affirms, is empowering and motivating. Our lives are projects, works of art—a dance, a painting, a musical score—that are never done.

Carl refuses to be defined by an unchangeable essence that precedes his existence and defines who he is. The motorcycle is a ‘freedom machine’ that celebrates, expresses and proclaims the absence of restriction, interference and constraint—and Carl seeks freedom from the roles that race, class and family prescribe for him.[6] In an interview on Toronto radio Clarke says that Carl, a visible black man on a sporty motorcycle, is a political statement: ‘I’m going where I want to go!’ While his peers are getting married and settling into routine jobs, Carl tries to escape convention and achieve his dreams—to lift himself above his circumstances and transcend his limited options, if only momentarily. His motorcycle represents that everything is possible—“if someone puts an obstacle in front of you,” Clarke asserts, “go around it!”[7] Carl’s motorcycle functions as a symbol of freedom and independence—the ability to go anywhere—in multiple ways.

Riding aims at personal freedom. Jonathan Goldstein says that the core of biker culture is the autonomous individual seeking freedom and adventure.[8] This is certainly true for Carl: riding allows him to pursue “liberation” (86). Where cars represent family and commitment, motorcycles provide solitude and independence (5). When on his motorcycle, pavement represents possibility: alleys become streets which become highways which become freeways leading away from the inner city of his life (4–5). The road is always taking him somewhere, “so long as the road is…more highway and freeway than…a strict street or—worse—a blankety-blank dead end” (3). The open road, however, also has parameters: it requires “navigating…over the potholes and the busted bits of truck tires and even broken parts of cars or dead creatures” (3)—the highways are “controlled by truckers and trolled by police” (6), and other vehicles constitute obstacles to avoid (14). On his motorcycle Carl experiences “floating, flying” and “feeling actually free” (86). Riding “gives Carl the sensation that he’s flying. Flying! Again.” And yet he worries—“will his wings be clipped—will he have to crash to earth” like Icarus? (259). Will he be grounded by circumstances beyond his control?

Carl’s motorcycle aims at personal adventure and pleasure. Riding is a cure for boredom, an expression of Carl’s “antipathy for ennui” (10) that enables him to escape the routines of daily life. “The BMW is an airship, uplifting him…from…other folk’s creeds and the dullard crowd,” from a life that “has been humdrum” (14–15). ‘Creeds’ represent the social beliefs and rules that constrain him and define who he is; ‘crowds’ symbolize the herd of ordinary persons, the railway worker struggling to make ends meet in a dull job of laundering (the same task at which his mother has labored for years). Carl seeks relief from “Discontent”—from being a guy who totes baggage and bedding for night-train sleeping cars (12). Atop his machine “he can escape, temporarily, the Drudgery that traps so many … Negroes” in dead-end lives (12)—even escape the monotony of monogamous sex. “Lovers can be frustrating and the railway job revolting. But the motorcycle attracts fresh, new candidates and delivers Carl always the possibility of fresh, new destinations” (38). Liz II lets him live in the moment; when on his bike, Carl’s “wage slavery” ends—“if only for today. Carl seeks Pleasure now—just sheer, reflex Happiness” (14).

Carl’s motorcycle aims at personal esteem and respect. It creates an image for him: “he buckles on the helmet; the red, yellow and white painted flames, licking back from the black face opening, look as proud…as the flag of any new African state” (12). Both the bike and Carl’s riding wardrobe provide self-respect, turning him—in his own eyes—into a suave, dapper and dashing macho male rather than a grade ten dropout blue collar black man. “Aboard that machine, he imagines that he’s Jesse Owens, streaking always to Victory, with style, with panache” (86). The motorcyclist image is also meant to impress others and attract lovers: “a (white) woman turns her head; she sees Carl…and she feels a twinge of arousal. So he hopes” (14). And yet the image is artificial and hollow; his shiny, sporty BMW is “just a pose”—“Liz II is just a prop. The machine props him up” (14). Carl’s persona is perhaps more appearance than reality, more shadow than substance—just like some motorcycle ‘posers’ today.

Carl’s motorcycle, finally, aims at social equality. Riding, Alan Pratt says, projects an outlaw image, sometimes even a sense of nihilistic rebellion that is contemptuous of the values the majority of society embraces.[9] Carl is not a member of a motorcycle gang or a ‘true nature’s child born, born to be wild’ who rejects all mainstream values. In fact he has middle-class aspirations—pleasure and wealth, belonging and respect, meaningful work. Carl’s non-conformity does not threaten civilized society, but he does abandon particular cultural values related to race and class that would keep him in his place. Riding—especially overtaking another vehicle—“is class warfare” (6). So is owning a flashy motorcycle: “after scrimping, scraping and scavenging for railway-job tips, Carl motors—masters—the first brand new BMW in Nova Scotia…. The machine enthrones him: black prince of the roads. He attains the great object: Majesty!” (11). He is no longer an under-class servant but upper-class royalty, no longer downstairs but upstairs. Riding is also an act of race warfare. Carl owns a first-class bike—horizontally-opposed two cylinder, four-stroke, four speed, 102 mph top speed—and “his purchase flouts Prejudice; his profile, astride the machine and gliding black leather and purple metal…must give whites-only segregationists serious heart attacks” (10–11). Maneuvering his motorcycle, Carl “may be colored, but not colonized, not totally” (12)—his bold machine “classifies [him] as the most incongruous…Negro in all Nova Scotia” (13). Carl also resists anti-black prejudice through seducing beautiful white women—what he calls “the Playboy school of Integration” (12–13). Motorcycle riding and sexual conquests are political statements against racism. Both activities free him from social expectations; “Carl wants a Greenwich Village, not Africville, existence; to have more than one woman—in more than one color” (38). The bike offers “Emancipation”—the possibility that he can “dump Halifax for New York City, Africville for Greenwich Village” (233). Carl is, finally, an intellectual. While “lugging suitcases at the Halifax train station, he whistles snatches of Debussy or fragments of Gershwin. Anything to lift him above the unlettered…herd. Carl loves Copland’s ‘Fanfare for the Common Man,’ but he sure don’t wanna be mistaken for one” (68). Eventually he leaves his railway job and attempts to establish himself as a self-supporting artist. The mobility of his motorcycle means, Carl hopes, social mobility beyond his reality.

In these various ways Carl’s motorcycle allows him “to recreate the Self” amid the contradictory forces in his life (13). “He’s a colored man, trying to negotiate a white world that wants him to be a safe, smiling servant, and black women who want him to be a respectable husband and a responsible father, raising clean children in a paid-off house. But what if he wants to be an artist? To escape the railway? To live more like Picasso and less like a preacher? What if he doesn’t want merely middle class, married, monogamous and mortgaged?” (168). Despite the expectations and constraints, Carl wants to live free and unfettered—a longing proclaimed by the fact that he rides a motorcycle rather than drives a ‘cage.’ And yet he feels the dissonance—wanting freedom yet recognizing that “he’s not stable: no settled career, no decided girl, no concrete Faith, no real direction.” He has nothing “to anchor him” (196). His own choices, he realizes, may not be fully authentic—only reactionary, focused on immediate gratification rather than long-term flourishing. Despite having a freedom machine, Carl never really goes anywhere—apart from a few Maritime excursions and a road trip to New York City, he remains in Halifax. Near the end of the novel one girlfriend miscarries a child, perhaps Carl’s, while another gives birth and names him the father. Unable to abandon the boy as his own father did him, Carl starts to wonder: could he be attached to a child? Committed to one woman? Or does he need the unbridled liberty of a motorcycle on an open road? The story ends with Carl caught between these two pulls: “where is his—their—pavement leading…now? Might he have Freedom and a family? What kind of Freedom? Which family?” (265) What is the life he wishes to create, the future he wishes to choose? These questions concerning the meaning of a good and worthwhile life, of course, are central to the human condition.

While The Motorcyclist is as much—if not more—about sexual encounters as riding experiences, it captures much about motorcycling. The thrill of racing a friend. The joy of meandering down a back road. The risk of ever-present death. The macho biker—or biker chick—image. Being one with the machine. The beauty of a tricked-out bike and wind-worn gear. The pleasing sound of a fine-tuned engine, loud pipes or a high whine and wheels on pavement. Most important, The Motorcyclist teaches us that life is what we choose within what we are given. It reminds us that life—like motorcycling—is a journey not a destination. “A motorcycle is about going; a car is about arrival,” Carl declares (17). A profound lesson of life that we all might take to heart.

Notes

[1] See David Jones, “Riding Along the Way: A Dao of Riding” and Graham Priest, “Zen and the Art of Harley Riding,” both in Bernard Rollin et al. (eds.), Harley-Davidson and Philosophy (Chicago: Open Court, 2006).

[2] See Jones, “Riding Along the Way” and David Walton.

[3] See Priest, “Zen and Art of Harley Riding.”

[4] See Bernard Rollin, “What are a Bunch of Motorcycles Doing in an Art Museum?” and Craig Bourne, “From Spare Part to High Art: The Aesthetics of Motorcycles,” both in Harley-Davidson and Philosophy.

[5] Jean-Paul Sartre, Existentialism and Human Emotions (New York: Philosophical Library, 1957).

[6] See Fred Feldman, “Harleys as Freedom Machines,” in Harley-Davidson and Philosophy.

[7] Clarke discusses The Motorcyclist with Matt Galloway on CBC Radio’s Metro Morning, online at www.cbc.ca

[8] See Jonathan Goldstein, “What Can Marx and Hegel Tell Us about Social Divisions among Bikers?,” in Harley-Davidson and Philosophy.

[9] See Alan Pratt, “Motorcycling, Nihilism and the Price of Cool,” in Harley-Davidson and Philosophy.

James B. Gould teaches in the Department of Philosophy at McHenry County College, Crystal Lake, Illinois. He has published over 30 articles in religion, ethics and higher education curriculum, including the article Make Today Count: Motorcycling as Memento Mori in IJMS. He has been riding for 45 years, since learning on his father’s 1963 BSA.

a profound analysis of motorcycle traveling from a profound intellectual.